Dear SEM

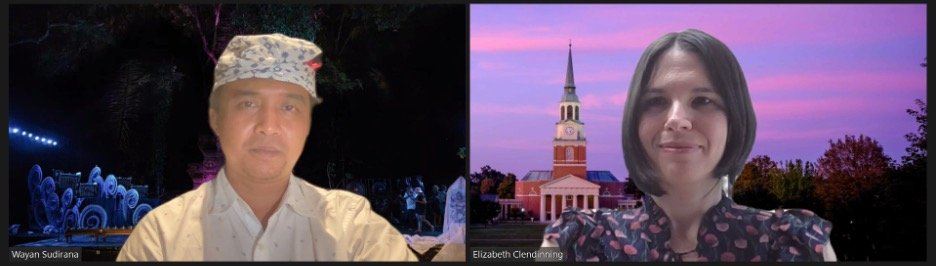

Dr. Elizabeth A. Clendinning, Dr. I Wayan Sudirana, Dr. Lauren Sweetman

Dr. Elizabeth A. Clendinning

Wake Forest University Dr. I Wayan Sudirana

Institut Seni Indonesia Denpasar Ten years after graduating from doctoral programs on opposite sides of the continent, scholars of Balinese performing arts I Wayan Sudirana (Bali, Indonesia; PhD ‘13, University of British Columbia) and Elizabeth Clendinning (North Carolina, USA; PhD ‘13, Florida State University) compare notes about the current state of ethnomusicology. They wrote out answers to the newsletter editors’ guiding questions separately, then met to discuss their reflections online.

I Wayan Sudirana (WS): A number of topics we wrote about are–

Elizabeth Clendinning (EC): Not exactly the same, but very similar. We both noted that the field has broadened in terms of areas of inquiry and methods of communication.

WS: Yes. The study of ethnomusicology has gone far beyond the definition I had understood at the outset. Because it is so progressive, it is difficult to define which studies are ethnomusicological and which are not.

EC: There is more intellectual crossover with media studies, languages, environmental studies, and computer sciences. Performance, filmmaking, poetry, museum exhibits, and other forms of communication are more broadly accepted as ways to share knowledge. All these ways of thinking or doing that seemed taboo when I was a student are now not only possible but celebrated.

WS: We need to accommodate new creative ideas as they present themselves. There are now many researchers without an ethnomusicology background doing ethnomusicology work, which makes the research conducted to be more dynamic. In Indonesia, for example, there is collaborative research conducted by the Geological Engineering Department of Gadjah Mada University and the Ethnomusicology Department of Yogyakarta Institute of the Arts about a traditional song (the song “Sulasih-Sulanjana” of the Dieng Society of Central Java) as a source of the creation of geothermal fertilizers.

EC: Wow, fascinating! But I would say that ethnomusicology still has special perspectives to offer about studying the relationships between people and sound. Disciplinary knowledge brought within the context of respectful interdisciplinary relationships seems key.

WS: Yes, and interdisciplinary work like this attracts industry interest and simultaneously brings back local knowledge. Maybe it’s time we no longer compartmentalize our fields and others. We should be open to all possibilities from all existing fields.

EC: On another subject—our hopes and fears for the future of ethnomusicology also seemed convergent. Both of us were concerned about equity, access, and representation of local knowledge.

WS: As a Balinese person who graduated from a university in North America, I still feel that Western supremacy is very dominant. This is troubling, given that many colleagues agree that we should be able to create a more balanced and enriched academic landscape.

EC: I agree that education and research in ethnomusicology doesn’t reflect our values and intellectual and creative traditions equally. I’d even say the field remains globally segregated, in large part due to language and economic resources. How is it fair that I can fly around the world on my institution’s dime and publish in my first language, when my colleagues overseas struggle to write and publish, in their third language, in journals that their libraries can’t even afford to access?

WS: More than that, when writing about topics that are common knowledge for us, we (Indonesian scholars) have to quote Western researchers, because they published about the topic first. Did those researchers ever consider whether publishing our common knowledge was ethical?

EC: Well, how can our generation, and the next generation, make it better?

WS: We should create a more balanced and enriched academic landscape. We should provide the widest possible opportunities for researchers from all over the world by eliminating supremacy and not discriminating against researchers based on their regional backgrounds, to be able to open positive academic dialogue for scientific developments in the field of ethnomusicology.

EC: Agreed. But I don’t think there is one single path forward. We all have unique gifts we can bring to share with our communities as researchers, artists, and teachers. It is up to all of us to envision a more equitable field and, step by tiny step, make it a reality.

WS: Regardless of all the problems we face, we must remain optimistic and think positively in all areas that we work on. We should stay focused and believe in the research we are doing. The development of human thought, global academic openness, and technological advances will open up positive opportunities for future developments in the field of ethnomusicology.

Dr. Lauren Sweetman

Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture & HeritageKia ora SEM!

It’s so nice to be writing again for SEM Student News, a publication near and dear to my heart. I was thrilled when Garrett and Hannah reached out to see how life has progressed post-degree. And what a ride it’s been!

Perhaps the biggest change for me was the move from North America (Toronto/New York) to live permanently in New Zealand, where I did my doctoral research. This move was not only a huge personal shift, but a professional one as well. I largely left behind the relationships and networks I’d worked to build over the course of my graduate studies, and found myself rebuilding my professional identity while learning a new academic environment and facing the realities of a much smaller, constrained academic environment with few (and no vacant) jobs in ethnomusicology (or music, or anthropology…).

I found myself taking a series of fixed-term contracts at a local university, teaching and conducting research on diverse topics outside of my area of speciality. Because my expertise was in ‘medical ethnomusicology’ (I did an ethnography of a Māori forensic psychiatry unit’s use of the performing arts), I was able to emphasize the ‘medical’ and ‘forensic’ portion of my work. I ended up teaching courses to undergrads primarily in health and working as a research officer on mental health studies. The academic environment was not kind, however. With difficulty piecing together full-time employment from a mish-mash of fixed-term contracts, the job insecurity was stressful. And, when I had my first son, I had no maternity benefits, sick leave, etc. etc. This, coupled with the desire to move back into the creative world, led me to seek a change.

In 2019, I shifted into the public service, and entered my current role in Research & Evaluation (R&E) at New Zealand’s Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. In doing so, I became aware of a whole world of research jobs and opportunities outside of academia that, when I was preparing for my career, I didn’t know existed. In my role, I conduct R&E focused on the cultural and creative sectors, providing insights to help inform evidence-based policy and decision making. It’s been interesting to learn how decisions are made in Government, and to see the impacts of those decisions on artists, creatives and practitioners in real time. It's also been interesting to see how research happens in Government—from scoping a project, to securing funding, to commissioning (often private R&E firms) to do the work, to quality assurance and publication—and to learn what types of evidence have the most impact.

Overall, my relationship to research has changed, from being an academic pursuit to being more functional, perhaps. My relationship with writing has changed too—it’s uncommon for researchers in Government to be named on publications; typically it’s Ministry of …. This is a big shift from the individual-author focus of my training, and at times it’s been challenging to let that sense of ownership go. At the same time, it’s somewhat freeing: I write as part of a team, and the default is to work collaboratively. Right now, for example, I’m working on developing a holistic model to evidence the value of New Zealand’s cultural system in collaboration with around 15 arts, culture, heritage, media and broadcasting, and sport organizations.

Moving into the future, it would be great to see more ethnomusicologists working in the public service and to explore how we can work better together with academia and other research practitioners. If you’re thinking of a career in ethnomusicology, I encourage you to apply your passion, skills, and knowledge both inside and outside of the academic contexts that are traditionally anticipated as the ‘road ahead’—there’s no telling where you could end up!